Kano, one of Nigeria’s most historically significant cities, boasts a rich legacy of architectural excellence rooted in tradition, culture, and an acute awareness of the environment. Located in the northern region of Nigeria, the city is characterized by its semi-arid climate, making it imperative for its builders to develop innovative methods to adapt to the challenging environment. Over centuries, traditional Hausa architecture in Kano has exemplified sustainable building practices, balancing form, function, and environmental harmony. As modern urbanization accelerates in Kano, revisiting these age-old practices offers vital lessons for creating environmentally conscious, resource-efficient structures.

Understanding Sustainability in Traditional Hausa Architecture

Traditional Hausa architecture in Kano was not only about building homes or public spaces but also about creating structures that aligned with the natural environment, social needs, and available resources. At its core, sustainability in these designs revolved around three pillars:

- Efficient Use of Local Resources: Builders relied heavily on materials that were abundant and easily accessible, such as mud, clay, and thatch.

- Adaptation to Climate: Designs were optimized for the region’s hot, dry climate, ensuring that interiors remained cool without artificial cooling systems.

- Integration with Social and Cultural Practices: Architecture served both functional and communal purposes, fostering social interactions and respecting privacy, especially in domestic settings.

These principles reflect a sophisticated understanding of environmental stewardship that is just as relevant today as it was centuries ago.

Locally Sourced Materials: The Bedrock of Sustainability

One of the defining features of traditional architecture in Kano is the use of locally sourced materials. These materials were not only sustainable but also uniquely suited to the environmental conditions of the region. Let’s explore some of these materials and their benefits:

1. Mudbricks (Tubali)

Mudbricks are the cornerstone of Hausa architecture. They are made by mixing clay, sand, and water, molded into blocks, and dried under the sun. This process eliminates the need for energy-intensive firing methods used in conventional brick production. The benefits of mudbricks include:

- Thermal Insulation: The dense composition of mudbricks helps regulate indoor temperatures, keeping interiors cool during the day and warm at night.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Since the materials are readily available, mudbrick construction is affordable and accessible to local communities.

- Eco-Friendliness: The production process has minimal environmental impact, with no emissions or deforestation involved.

2. Thatch and Wood

Thatch, made from dried plant material, and wood were commonly used for roofing. These materials provided excellent insulation while being lightweight and easy to work with. Additionally, they were biodegradable, aligning with the principles of environmental sustainability.

3. Lime Plaster

Walls were often coated with lime plaster, which provided a protective layer against erosion while enhancing the aesthetic appeal of the buildings. Lime is also a sustainable material due to its low energy requirements during production and its ability to absorb carbon dioxide over time.

Innovative Climate Adaptation Strategies

Kano’s semi-arid climate poses significant challenges, including intense heat, minimal rainfall, and occasional dust storms. Traditional Hausa architecture addressed these issues through ingenious design strategies that prioritized passive cooling and natural ventilation.

1. Thick Mudbrick Walls

The thick walls of traditional houses acted as thermal masses, absorbing heat during the day and releasing it at night. This natural insulation minimized temperature fluctuations, creating a comfortable indoor environment.

2. High Ceilings

High ceilings were a common feature in traditional buildings, allowing hot air to rise and creating a cooler living space below. This design reduced the reliance on artificial cooling systems.

3. Courtyards

Houses were often built around central courtyards, which served multiple purposes:

- Ventilation: Courtyards facilitated airflow, drawing cool air into living spaces and expelling hot air.

- Shade: The surrounding walls provided shade throughout the day, further reducing indoor temperatures.

- Social Interaction: Courtyards served as communal spaces for families and neighbors to gather.

4. Minimal Openings

Windows and doors were strategically placed to limit direct sunlight while maximizing cross-ventilation. This approach reduced heat gain and improved indoor air quality.

Water Management in a Semi-Arid Environment

Water scarcity is a persistent challenge in Kano, yet traditional builders developed effective strategies to manage this precious resource sustainably:

1. Rainwater Harvesting

Traditional buildings often incorporated systems to collect and store rainwater for household use. Roofs were designed to channel rainwater into underground storage tanks or surface reservoirs, ensuring a steady water supply during dry seasons.

2. Efficient Drainage Systems

Drainage systems were carefully planned to prevent waterlogging and erosion. Channels and soakaways were used to direct excess water into the ground, replenishing underground aquifers.

These practices highlight the foresight of traditional architects, who understood the importance of conserving water in a region where it is scarce.

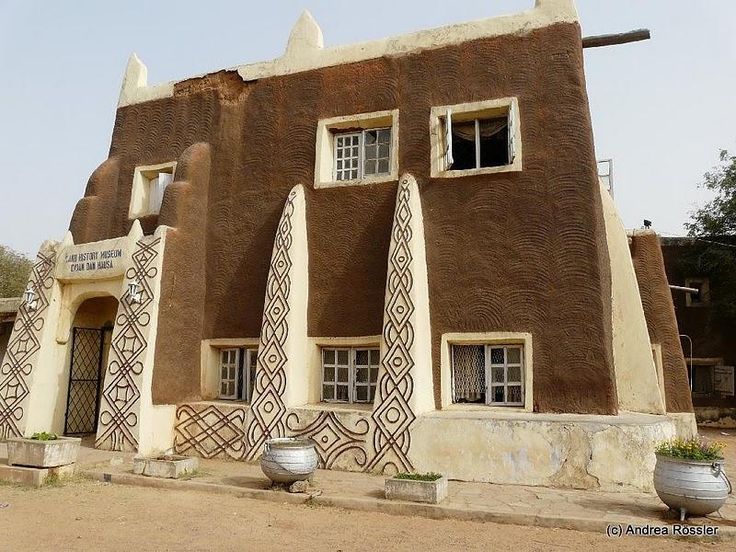

The Aesthetic and Functional Harmony of Hausa Architecture

Traditional Hausa architecture is as visually stunning as it is practical. Its unique aesthetic features are deeply intertwined with its functionality:

1. Geometric Patterns and Decorations

Walls and ceilings were often adorned with intricate geometric patterns. These designs were not merely decorative but also functional, as they helped diffuse sunlight and reduce heat absorption on exposed surfaces.

2. Domes and Vaulted Roofs

Domes and vaulted roofs were common in public buildings and mosques. These structures provided excellent ventilation and contributed to the iconic skyline of Kano.

3. Integration with the Environment

Buildings were designed to blend seamlessly with their surroundings, using earth-toned materials that harmonized with the natural landscape. This integration minimized the visual and environmental impact of construction.

Modern Implications and Lessons for Sustainable Development

As Kano undergoes rapid urbanization, many traditional practices are being replaced by modern construction methods that prioritize speed and cost over sustainability. However, revisiting these time-tested techniques can provide valuable insights for addressing contemporary challenges such as climate change, resource scarcity, and energy efficiency.

1. Adopting Local Materials in Modern Construction

Reintroducing the use of locally sourced materials like mudbrick and lime can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of construction projects. Modern techniques can enhance the durability and strength of these materials, making them suitable for contemporary applications.

2. Incorporating Passive Design Principles

Designing buildings with high ceilings, courtyards, and thick walls can reduce reliance on artificial cooling systems, lowering energy consumption and costs. These features are particularly relevant in Kano’s climate, where cooling demands are high.

3. Water Conservation Strategies

Rainwater harvesting and efficient drainage systems can be integrated into modern urban planning to address water scarcity. These systems are cost-effective and can be adapted for both residential and commercial use.

4. Reviving Traditional Craftsmanship

Preserving and promoting traditional building techniques can create job opportunities for local artisans while safeguarding cultural heritage. Training programs can help modern builders incorporate these techniques into contemporary designs.

Challenges and Opportunities in Revitalizing Traditional Practices

While the benefits of traditional Hausa architecture are clear, several challenges must be addressed to integrate these practices into modern development:

1. Perception and Preference

Many people associate traditional architecture with poverty or outdated methods, preferring modern materials like concrete and steel. Changing this perception requires public awareness campaigns highlighting the benefits of sustainable building practices.

2. Urbanization and Space Constraints

As Kano becomes more urbanized, the demand for high-density housing and commercial spaces poses a challenge for implementing traditional designs. Architects must adapt these practices to fit modern urban settings.

3. Lack of Skilled Artisans

The decline of traditional craftsmanship has resulted in a shortage of skilled artisans. Reviving these skills will require investments in education and training programs.

Conclusion: A Blueprint for a Sustainable Future

Kano’s traditional architecture offers a treasure trove of knowledge and practices that can guide sustainable development in the 21st century. By combining the wisdom of the past with modern innovations, architects and city planners can create buildings that are not only environmentally friendly but also culturally significant and aesthetically pleasing.

Sustainability is not just a buzzword; it is a necessity for addressing the pressing challenges of climate change, resource depletion, and urbanization. In Kano, the lessons from traditional architecture show that the solutions to these challenges may already exist within the city’s historic walls. Embracing these practices can help Kano build a future that respects its heritage while paving the way for a greener, more resilient tomorrow.

By learning from the past, Kano can lead the way in sustainable architecture, setting an example for other cities in Nigeria and beyond. The journey towards sustainability is a collective effort, and in Kano, it begins with a deeper appreciation of its rich architectural legacy.